Friendshoring Copper: A New Pillar of the U.S.-Brazilian Economic Partnership

The Issue

Brazil holds some of the world’s largest reserves of critical minerals, including niobium, rare earths, graphite, manganese, bauxite, zinc, and lithium. However, the next frontier is copper, which now accounts for one-third of all mineral exploration investment in the country. Market enthusiasm for Brazil’s copper aligns with a global outlook in which copper demand is projected to nearly double by 2035. China has already secured a strong foothold in Brazil’s mining ecosystem through trade agreements, concessional financing, and infrastructure investments. By contrast, the United States remains in the early stages of building a minerals partnership with Brazil. Unlocking Brazil’s potential as a major copper producer—and securing U.S. access to this strategic metal—will require bilateral efforts. Brazil must strengthen geological mapping, expand infrastructure, and streamline its overly bureaucratic permitting system. On the U.S. side, deploying strategic financing, promoting vertical supply chain integration, and offering targeted tariff exemptions to advance national and economic security objectives will be critical to a successful partnership.

Introduction

Brazil is home to a diverse basket of the mineral resources required for national, economic and energy security, with its reserves ranking first in niobium, second in both rare earth elements and graphite, third in manganese, fourth in bauxite, sixth in zinc (which is critical for the recovery of byproducts such as gallium and germanium), and seventh in lithium. In 2023, Brazil exported the second-largest amount of iron ore worldwide—$34.4 billion worth—amounting to 80 percent of Brazil’s $42.98 million total mineral exports.

Much of Brazil’s mineral wealth remains untapped. In 2024, it produced just 0.005 percent of global rare earths despite holding 23.3 percent of reserves, 4.3 percent of graphite with 25.5 percent of reserves, and 3 percent of manganese while possessing 15.9 percent of reserves.

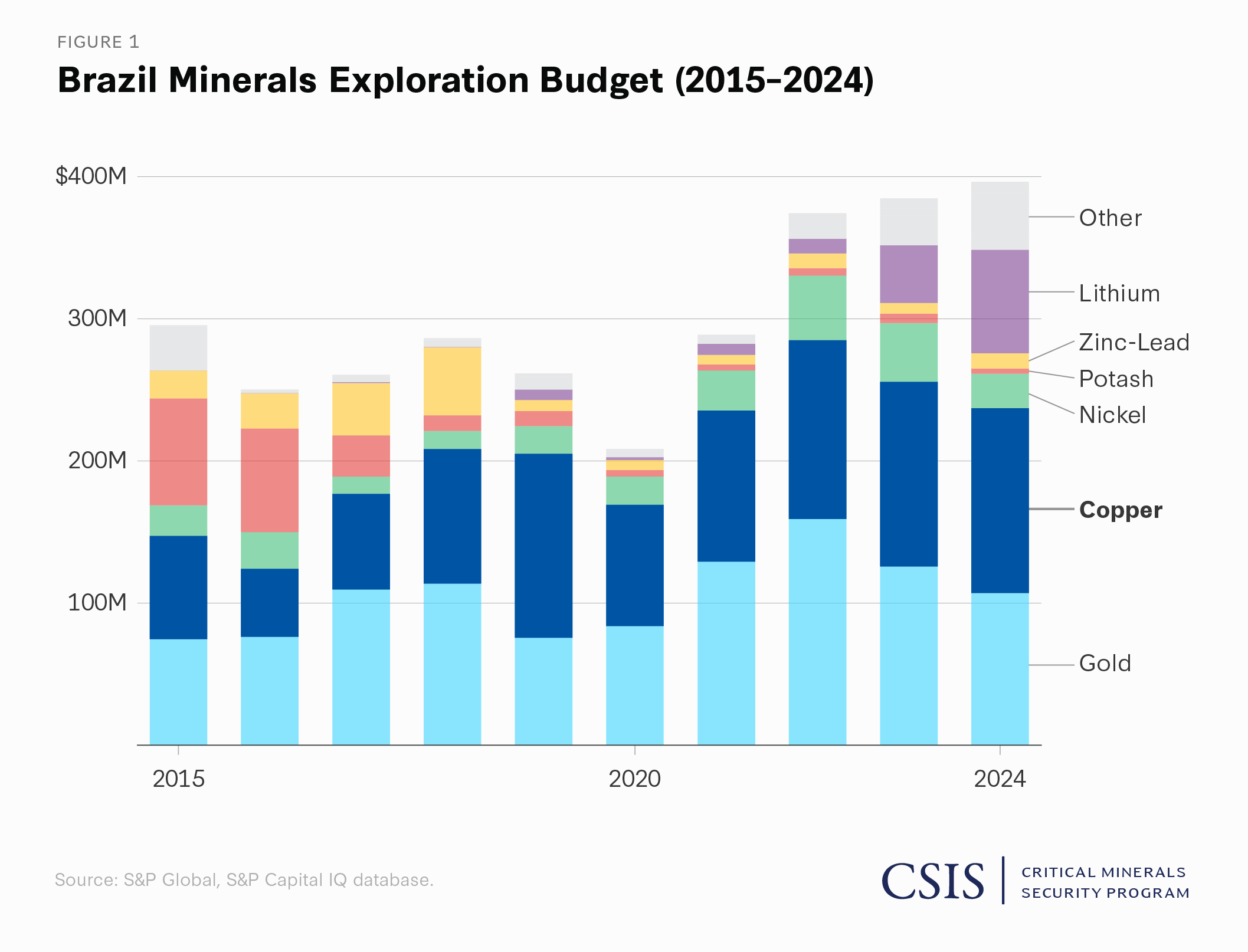

Nonetheless, Brazil has attracted significant attention from investors. According to S&P Global, in 2024, Brazil received $396.4 million in exploration investment, the eighth highest globally. This reflects a sharp upward trend in investor interest—between 2019 and 2024, Brazil’s exploration investment increased by 51.6 percent. Lithium exploration saw the most significant growth, rising from $7.4 million in 2019 to $107.1 million in 2024—a staggering 1,408.5 percent increase. Investment in rare earth element exploration also rose sharply, from $0 in 2019 to $13.3 million in 2024. Copper remained the largest source of exploration investment throughout the period, increasing slightly from $129.3 million in 2019 to $130.0 million in 2024.

Although Brazil produced only 1.9 percent of global copper in 2024, the metal has emerged as the country’s leading focus for mineral exploration. Copper accounted for nearly a third (32.7 percent) of total exploration spending in Brazil, underscoring the mineral’s emergence as a key frontier for future mineral development. It also signals strong industry confidence in Brazil’s untapped copper potential, despite less than 50 percent of Brazil being geologically mapped.

Market interest in Brazil’s copper is closely aligned with the global copper outlook. Estimates suggest that global copper demand will nearly double by 2035, increasing from just over 25 million metric tons in 2021 to approximately 49 million metric tons by 2035, with further growth expected to reach 53 million metric tons by 2050. Much of this demand is driven by artificial intelligence. Traditional data centers typically require between 5,000 and 15,000 metric tons of copper. However, next-generation facilities designed to meet the demands of artificial intelligence can require up to 50,000 metric tons of copper per site.

The successful growth of Brazil’s mining sector is deeply intertwined with the success of the Brazilian economy. In 2023, the mining sector contributed 86.2 billion BRL (roughly $16 billion) to the economy, provided direct employment to approximately 204,000 individuals, and supported an additional 2.3 million jobs indirectly. The sector also accounted for 4 percent of Brazil’s GDP.

Stimulating Western investment will be crucial to countering China. Critical minerals and the broader mining sector are poised to play pivotal roles in shaping the future of Brazil-China relations. In 2023, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, also known as Lula, proclaimed during a prominent state visit to Beijing that he wished to “raise the level of the strategic partnership between our countries, expand trade flows and, together with China, balance world geopolitics.”

China has been Brazil’s largest trading partner since 2009, with bilateral trade reaching a record $157 billion in 2023. Iron ore has traditionally anchored this relationship, and in 2024, it remained Brazil’s second-largest export to China by value, totaling $20 billion and accounting for nearly 70 percent of Brazil’s overall iron ore exports. This long-standing trade relationship has not only strengthened China’s steel industry but also bolstered domestic Brazilian mining giants such as Vale, a multinational corporation that started as an iron ore producer.

Today, as China seeks to scale its dominance in high-tech manufacturing—particularly in electric vehicle (EV) batteries, semiconductors, and permanent magnets—Brazil is emerging as a critical supplier of the inputs needed for these sectors. The country possesses significant reserves of the minerals required for these industries. Moreover, the infrastructure, technological capabilities, and institutional ties developed through decades of iron ore trade with China position Brazil as a natural partner for extending collaboration into other strategic minerals.

Beijing’s efforts to solidify this partnership are well advanced. Between 2007 and 2022, China invested nearly $4.5 billion in Brazil’s mining sector, accounting for more than 6 percent of its global outbound investment during that period. In 2024, CNMC Trade Company Limited (a wholly owned subsidiary of the Chinese-owned China Nonferrous Metals Mining Co., Ltd.) reached a $340 million deal to purchase the Brazilian rare earth producer Mineração Taboca. In 2025, Appian Capital Advisory completed a transaction that enabled the Chinese state-owned Baiyin Nonferrous Group to acquire the Brazilian mining company Mineração Vale Verde for $420 million. These acquisitions were followed by a visit from a high-level delegation of China’s National Development and Reform Commission aimed at securing access to energy transition minerals.

China is also moving to establish downstream capabilities within Brazil. BYD, China’s leading EV manufacturer, is building a production facility in Bahia, including repurposing a former Ford plant closed in 2021 that shut down due to mounting financial losses. Brazil has become a key market for BYD, with EV sales rising 85 percent to over 170,000 units in 2024—representing 7 percent of all new car sales in Brazil.

Through a strategic combination of financial investment, trade expansion, and political engagement, China is positioning itself to control Brazil’s supply chains end-to-end, from critical minerals to electric vehicle. Without a comparable commitment from the United States and its allies to deepen engagement with Brazil and support mining sector development, Brazil’s mineral resources risk becoming yet another pillar of China’s industrial dominance—potentially undermining Western supply chain security for key resources.

Diversifying investment is important to protecting the Brazilian economy. China’s economy has struggled to rebound after the Covid-19 pandemic. During the first quarter of 2025, imports of crude oil, iron ore, coal, and copper declined year-on-year, largely as a result of China’s sluggish economy. But attracting diversified investment will require Brazil to improve the ease of doing business, its regulatory environment, infrastructure, and environmental sustainability.

This paper offers an in-depth analysis of the opportunities and obstacles facing the development of Brazil’s mining sector, with a particular focus on the high-potential copper industry. It presents a set of targeted policy recommendations for both Brazil and the United States to catalyze growth in the sector and to enhance bilateral cooperation. For Brazil, proposed measures include (1) expanding investment in geological mapping, (2) increasing public infrastructure spending while enhancing incentives for private sector participation, and (3) streamlining mine permitting through centralized regulatory frameworks. For the United States, recommended actions include (1) deploying strategic financing through entities such as the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM), and the Department of Defense Office of Strategic Capital, (2) ensuring vertical integration to maintain control of production within allied supply chains, and (3) applying strategic tariff exemptions where they align with national security interests.

Copper: The New Frontier of Development

Brazil is considered to have significant untapped potential for additional copper discoveries through continued exploration. The average ore grade of the five largest copper mines in Brazil is 0.56 percent. For comparison, the average ore grade of copper reserves of the five largest copper mines in Chile is 0.62 percent, while the average ore grade of the five largest copper mines in Peru is 0.5 percent.

The Carajás region in Brazil holds considerable potential for additional copper discoveries. The average ore grade of the Pedra Branca operation in east Carajás is 1.530 percent, more than triple the average ore grade of the country’s five largest copper mines. There is also increasing interest in emerging copper prospects across Brazil’s western and southern regions. For example, copper-bearing granitic formations in the western state of Mato Grosso, as well as promising deposits in the neighboring state of Goiás, have drawn growing attention from industry stakeholders and exploration companies. Moreover, in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, the Brazilian Geological Survey has identified over 100 documented copper occurrences within the Rio Grande Copper Belt.

A number of projects are currently under development. The two largest operating copper mines in Brazil—Salobo and Sossego, both located in the northern state of Pará— are operated by Vale Base Metals, with Salobo in an expansion stage as of 2024. Bravo Mining announced the discovery of high-grade copper mineralization at the site of its Luanga platinum group metals project, also in the region of Pará, in 2024. Finally, in 2025, Lundin Mining announced an initial recovery of copper, gold, and silver at is Chapada mine, located in Goiás. It is the fourth largest copper mine in Brazil by deposit size.

Government Support to Brazil’s Mining Sector

The Brazilian government has launched several initiatives to foster a more conducive environment for mining investment and to position the country as a leading global supplier of strategic minerals specifically. In 2021, it introduced the Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy, a framework designed to accelerate the development of projects then hindered by Brazil’s traditionally slow and complex permitting and regulatory processes. As part of this initiative, an intergovernmental committee was established to fast-track the approval of strategic and critical mineral projects. As of 2024, the committee has approved 19 projects representing a combined investment of approximately $12 billion. The majority of these projects are located in Brazil’s Amazon region.

The Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy, originally launched under the Bolsonaro administration, has been sustained by the Lula administration, demonstrating the mining sector’s centrality to Brazil’s long-term economic development. In 2024, President Lula introduced the Mining for Clean Energy Program, aimed at enhancing geological knowledge and mineral research capabilities. As part of this initiative, approximately $10 million was allocated from the federal budget for strategic mineral mapping.

Additionally, in May 2024, the National Development Bank (BNDES) of Brazil launched a new fund to support critical and strategic mineral activity, targeting small- and medium-sized mining enterprises. Backed by 250 million BRL each from BNDES and Vale as anchor investors, the BNDES fund will finance mineral research, feasibility studies, and mine development, with a goal of raising an additional 500 million BRL from market participants.

To attract foreign investment and advance the build-out of strategic mineral supply chains, the government also announced more than 5 billion BRL in financial support through BNDES and the innovation agency Finep. This package includes credit lines for projects involving copper, nickel, lithium, rare earth elements, and other critical minerals.

While these policy measures reflect a growing recognition by the Brazilian government of mining’s strategic importance and signal a clear commitment to engaging the private sector, they remain fragmented and insufficient in scale. For Brazil to position itself as a global leader in mining over the next decade, a more coordinated and comprehensive national strategy will be essential to address persistent regulatory, financial, and infrastructure-related challenges.

Challenges to Developing Brazil’s Copper Industry

While Brazil’s copper reserves and recent discoveries offer a positive outlook for Brazil’s future copper industry, there are several obstacles the country must address before it can emerge as a major global copper and minerals producer. Specifically, Brazil’s complex bureaucracy, cumbersome regulatory environment, lacking infrastructure, and environmental challenges require policy intervention to create an enabling environment for the Brazilian mining sector.

Ease of Doing Business

Brazil’s mining sector often faces significant obstacles due to the country’s complex bureaucracy and heavy regulatory burdens, both of which pose challenges for business operations. In 2020, Brazil ranked 124th out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index, driven primarily by poor performance in categories such as obtaining construction permits and managing tax compliance. It also ranked 51st out of 82 countries covered in the business ranking environment by the Economic Intelligence Unit. The country’s tax system—particularly a company’s burden to stay compliant with tax rules—fared particularly poorly in the ranking.

There has been substantial improvement in Brazil’s investment climate for the mining industry. In the Fraser Institute’s 2023 Survey of Mining Companies, Brazil ranked 29th of 86 jurisdictions in investment attractiveness. Five years prior to that, in 2019, Brazil had ranked 46th out of 76 jurisdictions. Unfortunately, despite the increased attractiveness ranking, the country’s policy perception score declined by more than two points over the same years, placing it 43rd of 86 jurisdictions. Survey respondents cited growing concerns over uncertainty regarding protected areas (a 47-point increase in concern), community development requirements (up 37 points), and regulatory duplication and inconsistencies (up 23 points).

Regulatory Environment

Mine permitting in Brazil involves a multi-step process coordinated by various federal and state entities and is widely recognized as a major obstacle to investment in the sector. The system is marked by administrative inefficiencies, jurisdictional overlap, and prolonged approval timelines, particularly for projects situated in environmentally sensitive regions such as the Amazon. Several key government agencies play central roles in Brazil’s mining sector governance. The Ministry of Mines and Energy is responsible for formulating and implementing national policies related to energy and mineral resources. The National Mining Agency serves as the sector’s primary regulatory authority and is currently engaged in efforts to modernize the country’s mining regulatory framework. The Geological Survey of Brazil oversees geological mapping and the generation of geoscientific data to support resource development. Finally, the Ministry of the Environment is tasked with establishing and enforcing environmental regulations that govern mining and other industrial activities.

Brazil’s mining sector continues to face significant bottlenecks in the licensing process for exploration and extraction activities. The country’s permitting framework is widely regarded as overly complex, marked by overlapping jurisdictions and the involvement of multiple, at times competing, authorities across federal, state, and municipal levels. License applications can take up to 10 years to navigate their way through the bureaucratic system. As part of the 2021 Pro-Strategic Minerals Policy, the government committed to streamlining these procedures. However, as of 2023, officials from the Ministry of Mines and Energy—responsible for overseeing the National Mining Agency—reported a backlog of over 100,000 pending applications. This burdensome bureaucracy, coupled with limited transparency on tax obligations, contributes to the so-called “Brazil Cost,” an additional cost of doing business in the country estimated at 1.7 trillion BRL annually, or approximately 19.5 percent of the national GDP.

In July 2025, the Brazilian Congress approved the General Environmental Licensing Law (PL 2.159/2021), a landmark reform intended to modernize and streamline the country’s environmental permitting system. After more than two decades of debate, the legislation is now awaiting presidential approval. If enacted, it is expected to significantly accelerate approvals for priority projects, including those in the copper sector, by reducing bureaucratic hurdles and promoting greater investment in strategic industries.

One of the law’s most notable features is the introduction of the Special Environmental License, which allows fast-track approval within 12 months for projects deemed “strategic” by the federal government, even if they pose high environmental risks. Additionally, the legislation exempts certain activities from licensing requirements altogether, including road expansions, agricultural operations, water and sewage treatment, and small irrigation dams.

The law also introduces mechanisms to simplify ongoing compliance. Licenses may now be renewed through self-declaration, provided there are no changes to the project or applicable regulations. Furthermore, the legislation expands the use of nationalized self-declaration, enabling entrepreneurs to certify regulatory compliance online without prior review, building on practices already adopted in some states.

Another major shift under the law is the decentralization of a permitting authority. Responsibility for environmental licensing will be transferred from federal entities, such as the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources and Brazil’s National Environmental Council, to state and municipal governments. In tandem, the role of federal environmental agencies will become more consultative, with reduced binding power in the decisionmaking process. Collectively, these reforms aim to create a more efficient and investment-friendly permitting environment across Brazil’s mining, agriculture, and energy sectors.

Infrastructure

Brazil’s infrastructure remains largely insufficient to support large-scale critical mineral and copper mining, resulting in elevated logistics and energy costs for the private sector. Over the past two decades, Brazil’s public investment in infrastructure has consistently fallen below both regional and income-group benchmarks. Between 1995 and 2015, public investment in Brazil averaged approximately 2 percent of its GDP. This was significantly below the average of 6.4 percent for emerging market economies worldwide and 5.5 percent average for Latin American countries. In 2021, just 1.57 percent of Brazil’s GDP was invested in infrastructure and, by 2022, the Ministry of Infrastructure’s budget was the lowest share of GDP in 11 years. In comparison, Brazil spent 2.34 percent of its GDP on infrastructure in 2013, with an earlier average of 5 percent in the 1980s. In 2019, the World Economic Forum ranked Brazil 78th out of 141 countries in overall infrastructure quality.

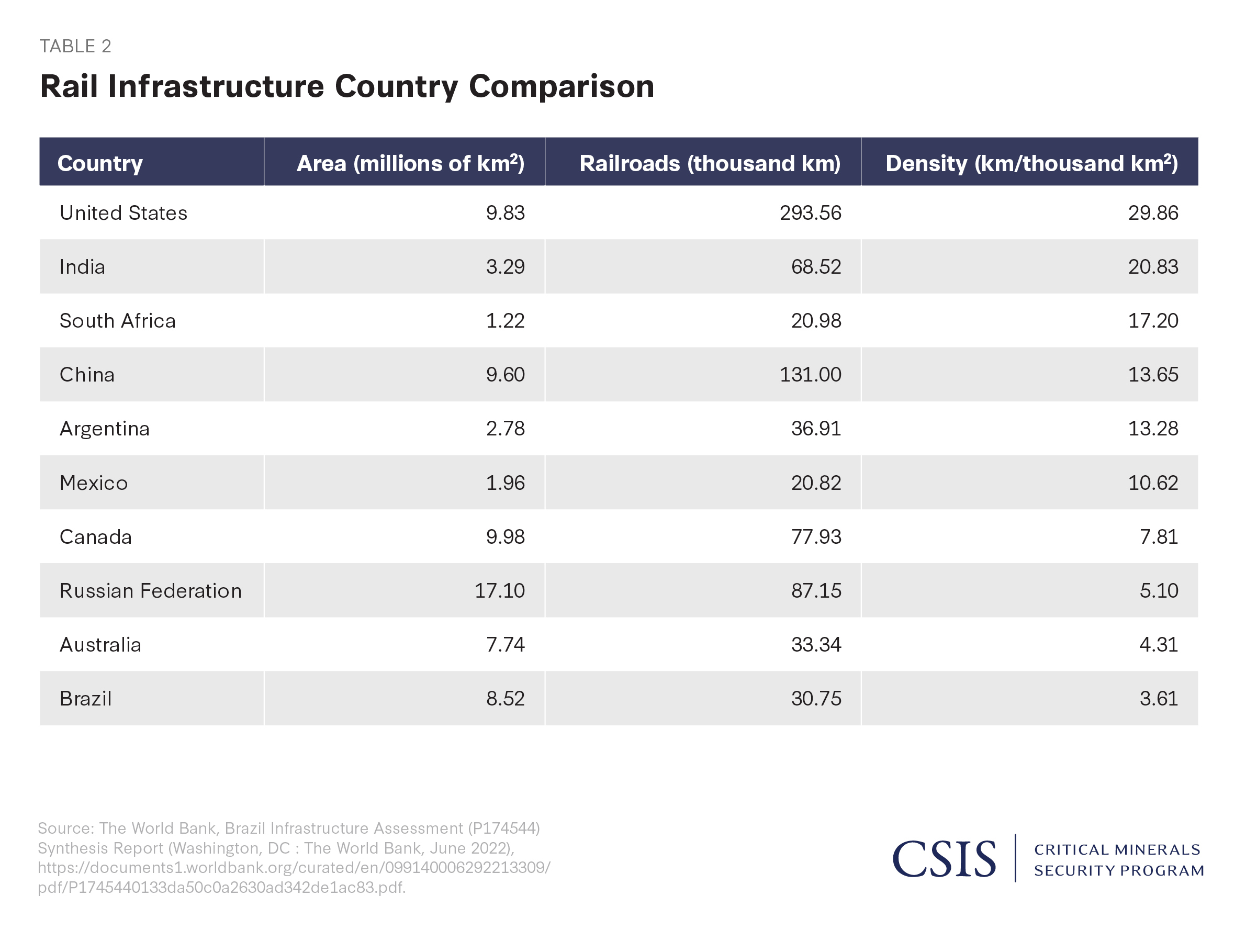

Brazil’s road infrastructure remains in critical need of improvement. Currently, only approximately 12 percent of the national road network is paved, and 85 percent of highways consist of a single lane for both directions of traffic. Although Brazil remains heavily dependent on road transport, the share of cargo moved by rail increased between 2010 and 2020, with iron ore accounting for nearly 74 percent of all rail freight as of June 2024. The national railway network spans 31,299 kilometers, but only about 10,000 kilometers are actively used for commercial operations. With just 3.61 kilometers of railway per 1,000 square kilometers of land, Brazil’s rail density remains low relative to other large countries.

Transport costs in Brazil are estimated at 11.6 percent of GDP—three percentage points higher than the average for the nearly 40 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—further contributing to higher copper production costs.

Infrastructure challenges are particularly acute in mining regions within the Amazon. Mining operations there rely heavily on the Carajás railway, a nearly 900-kilometer line connecting the Carajás mineral province in the eastern Amazon to the Port of São Luís on Brazil’s northeastern coast. Operated by Vale, the railway has a transport capacity of over 200 million tons annually. However, to accommodate future production increases under the New Carajás Program, further upgrades are required. In response, in 2024, Vale signed a $340 million agreement aimed at enhancing locomotive capacity and operational efficiency along the line.

Expanding and modernizing rail infrastructure in mining regions is essential for attracting additional investment and ensuring the viability of new projects. Yet infrastructure development efforts have often encountered significant obstacles. The Transnordestina Railway—intended to improve mineral logistics across Brazil’s northeastern region—has faced prolonged funding delays, construction setbacks, and substantial cost overruns. Despite nearly two decades of development and an estimated 15 billion BRL in investment ($2.8 billion) as of June 2025, the railway remains incomplete with no clear timeline for completion.

In addition to the logistical constraints involved in transportation, Brazil’s energy infrastructure poses considerable challenges to mining operations. While the country benefits from a predominantly renewable energy matrix—over 85 percent of its electricity was generated from renewable sources in 2022—including hydropower, this reliance makes the system particularly vulnerable to droughts, which can lead to energy shortages and price volatility.

Energy access issues are particularly pronounced at mine sites located in remote states such as Pará in the north, Minas Gerais in the southeast, and Mato Grosso in the center-west. Long distances between mine sites and major power generation centers often result in transmission constraints and supply disruptions. In these cases, companies are frequently forced to rely on diesel generators, further increasing operational costs and carbon emissions. Addressing Brazil’s infrastructure deficits will be critical to unlocking its mineral potential and positioning the country as a competitive global supplier of critical minerals.

Environmental Concerns

The location of Brazil’s copper resources within the Amazon rainforest, as well as two high-profile mining dam disasters in 2015 and 2019, have elevated environmental, health, and safety concerns with new mining projects, creating complications for the burgeoning industry. For Brazilian mining projects to have long-term success, the Brazilian government, in partnership with the private sector, must address the environmental and social concerns of indigenous and local communities.

Much of Brazil’s copper and mineral wealth is believed to lie within the ecologically sensitive Amazon rainforest. The Amazon is home to dozens of indigenous groups with close spiritual ties to the land. Mining projects close to ancestral lands require consultation and consent from the communities in question, a process which can, at best, add significant delays to new mines. Local groups across Brazil have traditionally been averse to the development of new mines, citing fears of potential impacts. In 2021, Anglo American withdrew 27 mining research permits in the Amazon, including 13 copper mining research permits on Sawré Muybu land, due to a months-long pressure campaign by indigenous groups.

Additionally, large-scale mining dam disasters have left local communities acutely aware of the tragic consequences of mining projects that do not have proper environmental and safety protections in place. On January 25, 2019, a tailings dam at the Vale’s Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine in the city of Brumadinho ruptured and collapsed, unleashing a tidal wave of industrial sludge that killed 270 people, mostly mine employees. It was one of Brazil’s worst industrial disasters and the largest tailings dam collapse in the world. The incident sparked intense outrage, exacerbated because just five years previously, in 2015, another Vale subsidiary—Sarmarco, a joint venture between Vale and the Australian company BHP— experienced another tailings dam collapse at the nearby city of Mariana, killing 19. On top of the tragic loss of human life, the two incidents have had long-term environmental and economic consequences, including polluting waterways, contaminating soil, destroying habitats, killing aquatic ecosystems, displacing communities, and devastating livelihoods.

Brazil’s mining legacy of environmentally complicated projects located in the Amazon rainforest, combined with its recent experiences with the hazards of mining failures, has led to a renewed commitment by Brazilian authorities to more heavily regulate the mining industry. Following the 2019 Brumadinho disaster, lawmakers banned the construction of new upstream tailings dams—used to store mining waste—and mandated the phasing out of the ones currently in use. In 2022, Vale announced that it would decommission 12 of its 30 tailings dams by the end of the year. The company also adopted the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management in 2022, and has enhanced monitoring and safety measures to ensure the tragedies of Brumadinho and Mariana are never repeated.

Policy Recommendations: Brazil

The policy recommendations for Brazil’s government largely center on expanding public spending to catalyze greater investment in the mining sector. In particular, increased fiscal outlays will be required to support comprehensive geological mapping and to scale up investment in critical infrastructure.

· Bolster geological mapping efforts. Significant portions of Brazil remain geologically underexplored. As of 2022, only 49 percent of the national territory has been mapped at the 1:250,000 scale, and just 27 percent at the more detailed 1:100,000 scale that is required to accurately assess the viability of mining projects. Copper-rich areas within the Amazon basin are particularly deficient in geological coverage relative to other regions. This lack of comprehensive geoscientific data impedes informed investment decisions, elevates project risk profiles, and ultimately deters capital inflows into the sector.

The Geological Survey of Brazil has identified 73 high-potential areas for strategic minerals mapping. However, the plan to map these areas is scheduled to take a decade to complete (2025–2034) and will still leave strategic areas unmapped due to budget constraints and the limited operational capacity of the Geological Survey of Brazil. Though the United States and Brazil initiated a pilot-scale project to carry out joint geological mapping and research in three regions in 2024, the project is expected to be limited in scale and centered on regions focusing on rare earths, lithium, and niobium mining.

· Invest in infrastructure. While private sector participation in cofinancing infrastructure is feasible, placing the full financial burden on mining companies can discourage investment, particularly when firms are expected to shoulder the costs of energy, transportation networks, and mine development. Currently, as mentioned above, less than 2 percent of Brazil’s GDP is allocated to infrastructure, significantly below the 6.4 percent average for emerging market economies and the 5.5 percent average for Latin America. Increasing public expenditures to develop investment will be crucial to stimulating investments in the private sector, particularly for greenfield projects.

Nonetheless, tax incentives and subsidies can stimulate private infrastructure investment. Brazil already offers some incentives, including the Special Incentives Regime for Infrastructure Development which suspends taxes on the import or sale of new equipment, construction materials, and services for infrastructure projects. These incentives could be further bolstered with an investment tax incentive, directly offering a tax break for foreign or domestic companies investing in large-scale infrastructure projects accompanying a mining project.

· Reform permitting processes. Centralizing Brazil’s permitting and licensing processes could substantially reduce corruption, streamline bureaucratic procedures, and accelerate project approvals. Currently, mine permitting involves a fragmented, multi-tiered system managed by a range of federal, state, and municipal authorities. This complex framework is characterized by administrative inefficiencies, jurisdictional overlap, and protracted approval timelines, and poses a major barrier to investment, particularly for projects in environmentally sensitive areas such as the Amazon. License applications can take up to a decade to move through the system, undermining investor confidence and delaying project development.

Indonesia presents a good model for reform. Under Law No. 3 of 2020, which amended the 2009 Mineral and Coal Mining Law, Indonesia transferred exclusive authority for mining permits to the central government. This reform has helped streamline permitting, reduce bureaucratic delays, and mitigate corruption at the subnational level. It also introduced mechanisms to facilitate permit transfers and corporate restructuring through approval by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, thereby improving transparency and enabling more efficient investment transactions. Brazil could benefit from adopting similar centralization measures to create a more predictable, transparent, and investor-friendly regulatory environment.

Policy Recommendations: The United States

· Deploy strategic financing for Brazilian mining projects with vertically integrated supply chains involving allied processing and manufacturing partners. Vertical integration is essential to ensure that U.S.-backed mining projects do not ultimately funnel raw materials into Chinese-controlled processing and manufacturing. Integration across the value chain must be a core consideration from the outset of project planning. A cautionary example is the U.S.-led Minerals Security Partnership’s support for Brazil’s Serra Verde rare earth project, which produces both the light and heavy rare earth elements critical for magnet production. Despite this strategic backing led by the United States, it was later revealed that the project’s offtake had already been contracted to Chinese entities, owing to China’s near-monopoly on heavy rare earth refining—a gap that should have been addressed during initial structuring.

· Increase utilization of the DFC for strategic minerals and infrastructure projects. In 2024, China’s Belt and Road Initiative spent nearly $22 billion in the mining and metals sector. To counter China, the United States will need to spend more. One of the DFC’s first successful transactions in the mining sector was in Brazil when it made an equity investment of $30 million in TechMet, which holds 70 percent ownership of the Piauí nickel project in northeast Brazil. That endeavor is set to produce 27,000 metric tons of nickel and 900 metric tons of cobalt by 2028. Furthermore, in late 2024, the company owning Piauí (Brazilian Nickel) stated that it had been offered a $550 million loan from the DFC for the project. Shortly thereafter, in 2025, Brazilian Nickel announced a supply agreement with Electro Mobility Materials Europe, a France-based battery materials processor, to supply nickel from its Piauí mine in support of Western EV supply chains. The Piauí project exemplifies how targeted U.S. financing can help advance Brazilian mining projects to provide inputs for allied battery-value chains.

· Leverage the EXIM through its Supply Chain Resilience Initiative. Through programs such as the China and Transformational Exports Program and the Make More in America Initiative, EXIM is playing a key role in advancing the reshoring, nearshoring, and friendshoring of critical supply chains. This includes providing financing for critical mineral projects that lessen dependence on China, as well as supporting the development of infrastructure and processing capacity consistent with the objectives of the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative.

· Utilize financing from the Department of Defense’s Office of Strategic Capital to support strategic projects in Brazil. Developing greenfield projects is a complex, capital-intensive, and equipment-heavy endeavor. Offsetting these expenses—particularly for rare earths—will be critical to securing an adequate amount of feedstock.

· Consider strategic tariff exemptions. Strategic tariff exemptions serve as important instruments for aligning national security imperatives with the goal of sustaining resilient and cost-efficient supply chains. By carving out exemptions for key allies and economic partners—particularly surrounding critical mineral supply—the United States and Brazil can avoid the adverse effects of blanket tariffs that may otherwise disrupt material flows, raise input costs, or strain downstream industries. For instance, excluding countries with aligned economic and security interests from tariffs on inputs such as copper or rare earth elements helps safeguard access to vital resources while preventing foreign adversaries from capturing a greater share of these mineral markets. These targeted exemptions can reinforce diplomatic and trade relationships and encourage joint investment in processing and manufacturing capacity within allied jurisdictions. When carefully structured, such tariff policies support economic security and strategic resilience.